When we encounter the 1929 portrait by Bernard Boutet de Monvel of the last Maharaja of Indore (titled Portrait of Maharaja Yeshwant Rao Holkar II in Western Dress), we find something quite extraordinary. Holkar II wears a tuxedo jacket, crisp white shirt and bow tie, his cape draped elegantly, his gaze neither triumphant nor regal in the traditional sense but quietly confident, even pensive. His tall, slender form and long, tapered hands, the angularity of his jawline, the elegance of posture, all convey an aesthetic of refinement rather than assertion. He is affluent, undeniably, but not blustering; his quiet elegance betrays a sense of fragility, a melancholy maybe, or at least an introspective distance. The picture refuses the flamboyant emblems of a maharaja and instead gives us an aristocrat of the modern era, someone who has adopted Western dress, Western manners, Western aesthetic discourse, and in doing so, announces that he is not only Indian princely power but also part of a global design–driven elite.

That portrait, in its elegance and ambiguity, is the perfect prologue to Holkar’s aesthetic project: he did not simply inherit a throne, he inherited a mandate to bridge worlds. He took Western design language, through his education, his travels, his friendships, and brought it back to India, transforming not just interiors or jewellery, but the very notion of what a maharaja could be.

From his teens he was sent to England for schooling (Charterhouse, then Oxford) and returned to India at age 17 to assume the throne in 1926. Then, immersed in the Paris-London-New York avant-garde of the late-1920s, he met figures like Henri‑Pierre Roché (who introduced him to the art world), and was exposed to the fresh currents of modernism. In Paris he encountered Jacques Doucet, the haute-couture and art patron, whose decors and collection fascinated him. As one writer described: “The West has always been inspired by the East… but this young guy was one of the very few to do the inverse.”

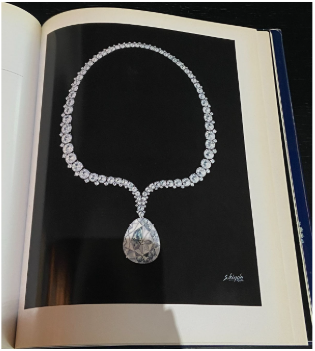

In those circles, the young Maharaja cultivated taste. He and his first wife, Sanyogita Devi Holkar, moved among Parisian salons and collecting trips, photographed by Man Ray, commissioning portraits by Boutet de Monvel, acquiring jewels at Chaumet and Mauboussin, acquiring modernist furniture and sculpture.

His art-collection phase was swift but intense. He acquired works by leading figures of modernist design, furniture by Eileen Gray, Émile‑Jacques Ruhlmann, sculptures by Constantin Brâncuşi, and he planned a temple for Brâncuşi’s Bird in Space for his palace. He didn’t merely collect in a compartmentalised way: architecture, furniture, jewellery, cars, social life all fused into a lifestyle of modern princely cool.

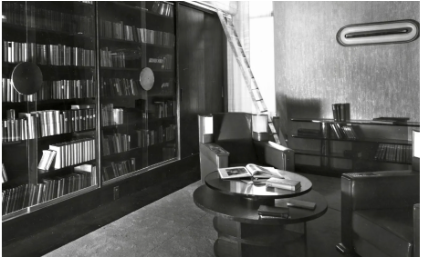

Then came the turn of the early 1930s and the great global economic crisis. Most princes would retreat into lavish traditional palaces; Holkar instead commissioned his palace at Manik Bagh Palace (“Jewel Garden”) in Indore (1930-33) from German architect Eckart Muthesius, still in his twenties, creating a total work of art (Gesamtkunstwerk) of modernism in India: tubular steel furniture, carpets by Ivan da Silva Bruhns, lighting by Jacques-Émile Ruhlmann, glass-paneled walls, air-conditioning: features of a house mapping Europe’s design ahead of its time.

Manik Bagh by AD INDIA

Yet, none of this means Holkar was shallow or simply a socialite. His collection, travels, commissions, relationships with artists were grounded in a sincere belief in design as freedom. He was born heir to a throne - so his life from early on involved expectation, constraint, duty. But by turning his energies into collecting and patronage, into enlisting the avant-garde, he reframed that inheritance. Art and architecture became his expression of autonomy, a way of defining rule on his terms. He was not just a prince; he was a cultural actor.

In his later years the political tides turned: Indian independence, the merging of princely states, loss of formal power, but the aesthetic legacy remained. He settled on the Côte d’Azur, at Villa Ushavillas in Villefranche-sur-Mer, a residence that distilled his lifelong pursuit of serenity through design. The villa, all white surfaces, light-filled rooms, and sculptural furniture, was conceived not as a statement of status but of introspection. It translated the aesthetic logic of Manik Bagh into Mediterranean modernism, geometry softened by sea air, minimalism tempered by human warmth.

And though the politics of India had shifted irrevocably, the aesthetic legacy remained. The 2019–2020 exhibition “Moderne Maharajah” at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris brought his vision back into focus, assembling over 500 pieces from his commissions and collections — many now held by the Al Thani Collection Foundation. Seen together, the Manik Bagh furniture, the Cartier jewels, the portraits, and even echoes of Villa Ushavillas formed a seamless narrative: the life of a man who built an empire of taste.

And so his portrait in Western dress is more than an image: it is the signal of a life that re-wrote what princely luxury could mean. He looked fragile and aesthete-like, not warlike or ostentatious; but the fragility signalled self-awareness, the aesthetic sense signalled cultural ambition. That he turned Indian royalty into a node of global design dialogue is his authentic legacy.

In sum: when you look at the portrait, look again at his collection, look again at the palace he built. It is not about power in the conventional sense, but about taste, about connection, about a refined kind of authority. Holkar’s authenticity lay in his refusal to replicate tradition, and instead to interpret it through the lens of modernity. And that is why his influence on design and luxury remains today.